Developing—and choosing between—book ideas

A look at the earliest steps in my story development process

Today I’m going to tackle another subscriber question. Julie asked:

How do you come up with story ideas and how do you choose which one to write next? Where/how do you save ideas for later?

I love this question because it focuses on a part of the creative process that I haven’t covered much: the ideation phase.

I have a LOT of book ideas. Literally hundreds. But most of these ideas are so vague/broad that I am nowhere near ready to sit down and draft them. I’m not even ready to truly brainstorm them. So how do I keep track of everything? At what point do I decide to seriously pursue an idea?

It starts with what I think of as a predecessor to an actual story idea: a story kernel.

Story kernels

A story kernel is a piece of a larger idea, not yet capable of growing into an actual book. Why? Because this kernel—part of a seed—is dormant or lacking. It hasn’t germinated yet, often because the idea is missing some crucial story-telling element that will let it sprout.

For my story ideas to sprout, I typically need a setting (world), problem (plot), and someone trying to solve said problem (protagonist).

Most of my kernels have the potential to sprout, but for now, they are resting and waiting for that growth to begin.

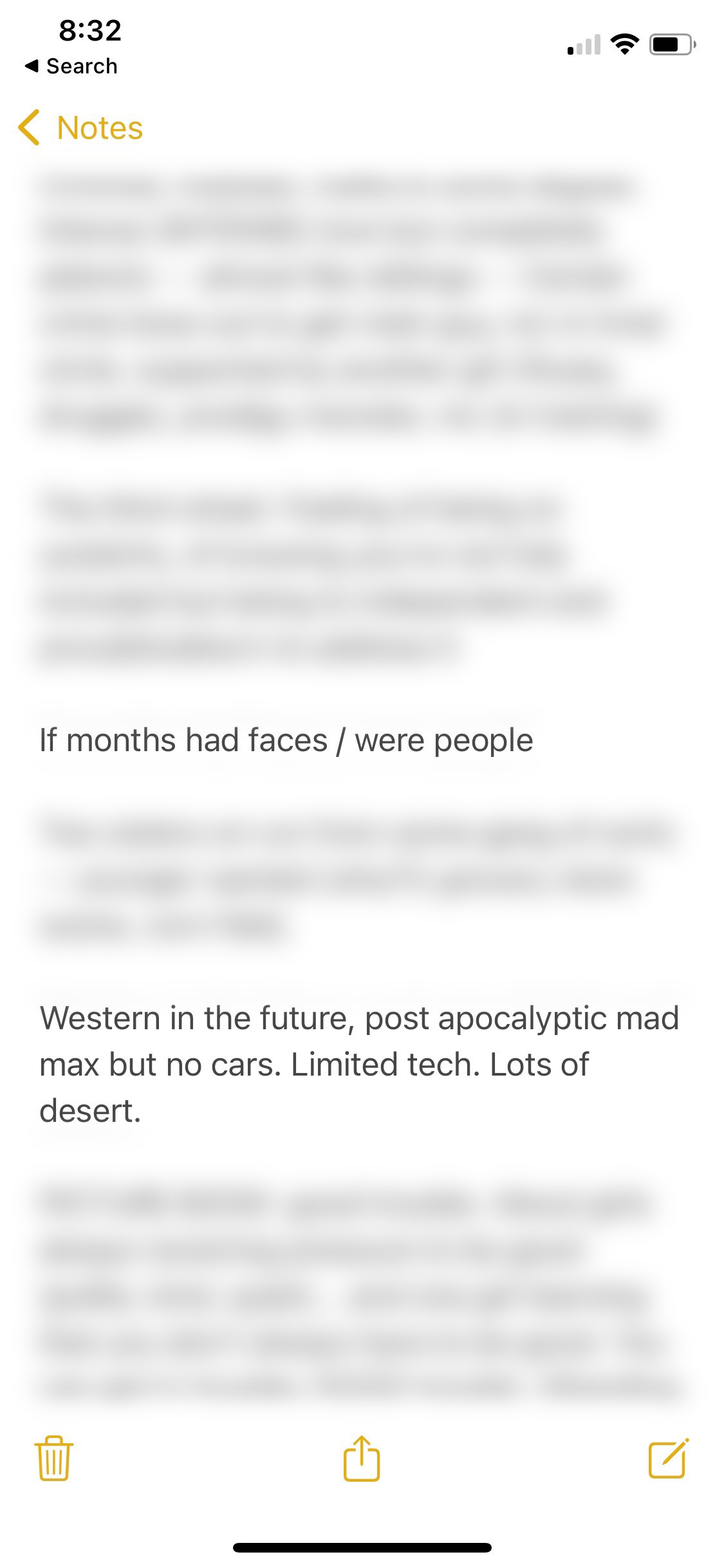

Sometimes my story kernels are just a setting—a location that I can see in my mind or some extremely detailed world-building note about an even bigger world I can’t yet see clearly. Sometimes a kernel is a single scene: two characters doing something, a random inciting incident, the glimpse of a climax… but no greater plot. Sometimes the kernel is just a top level concept, like “If months had faces / were people.”

I keep all my story kernels in a single document in the Notes app on my phone. And yes, the above concept example is one of the things currently saved in that document, as you can see in the below screenshot. You can also see the initial story kernel that went on to eventually became Dustborn.

I add to this document when new ideas come to me, and I scroll through it every few months to see if any of the ideas speak to me or grab me with renewed enthusiasm.

This is the one time in my creative process where I promise myself to not think critically at all. Literally everything gets written down. There are no bad ideas. I never delete things. I do sometimes reorder them, so ones I’m less interested in are at the bottom, but I tell myself that every kernel has potential, even if I can’t see it yet.

Story ideas

If I keep thinking about one of those kernels, it will inevitably start to germinate. Suddenly, the idea will have that magic trifecta (world + character + problem/plot), and now that it’s sprouting, it’s too big for the Notes app. It needs a bigger pot, so to speak.

Enter: a dedicated notebook.

“Dedicated” means the only thing allowed in this notebook are ideas for this particular story. I will plot in this notebook, flesh out characters, worldbuild, draw maps, sketch locations, write scenes longhand, ask myself lots of questions. Anything and everything.

I like having an analog place for this type of thinking. I’ve found that working on the computer feels so formal. It’s too easy to overthink things, get stuck in editing circles, or simply stall out. But there is something freeing about being able to brainstorm in analog. Nothing is final. It’s very open. Paper is where you can experiment without any pressure.

says it best in Steal Like an Artist, when he advocates for having a digital and analog split to your office and/or process:“The computer is really good for editing your ideas...but it’s not really good for generating ideas. There are too many opportunities to hit the delete key. The computer brings out the uptight perfectionist in us—we start editing ideas before we have them.”

Amen.

If you want a better peek at some of my notebook pages, you can click through to these insta posts:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to From the Desk of Erin Bowman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.